We have a guest blogger here today to discuss edible Roses and what you can do with them.

Divers Pretty Things Made Of Roses & Sugar

by Mistress Renata Kestryl of Highwynds

The 1552 edition of Banckes Herbal contains a woodcut of three Tudor roses, a crown and a ribbon banner proclaiming the rose to be “The Kynge of floures” an opinion that seems to be shared by the people of 16th century England. Of course, the rose was the symbol of the royal family, but it was also a favorite embroidery motif, probably the most common floral motif in use at the time.

Herbalists and the writers of household recipe books were also fond of roses. John Gerard, whose Generall Historie of Plantes was first published in 1597, devotes no less than twelve pages to the description and virtues of roses, far more that he gives to any other herb. (The title of this article comes from his description.) Sir Hugh Plat, who published his Delightes for Ladies in 1609, has 16 recipes for preserving roses in various forms.

The recipes (or “prescriptions”, as the herbalists like to call them) are for things like rose-water, rose oil, rose honey or sugar, rose syrup and conserve of roses. All these item were used for cosmetic, medicinal and/or culinary purposes. Rose products were thought to be good for the skin, cooling and soothing to the digestive and the respiratory systems, and gentle enough that even the very old and the very young could tolerate them.

A disclaimer: While these treats were used medicinally in the 16th century (some examples follow each recipe), these recipes are not meant for anything other than culinary uses.

Harvesting Rose Petals

Warning: Most roses today are grown for ornamental purposes, and are usually treated with chemical pesticides and systemic rose food. While these help the rose plant produce more and healthier flowers, they make the flowers extremely toxic. Therefore, it is very important that no chemical pesticides or systemic rose food have been used on the rose plants for at least one year before harvesting for human consumption. You can be sure of this by a) growing the roses yourself in your own garden (but keep an eye on your gardener, if you have one — often they will feed your roses every year without mentioning it to you) or b) knowing the person who does the growing. If you are not 100% sure, do not use the roses.

Having made sure of the non-toxicity of the petals in question, they should be picked in the early morning, after the dew has dried. Cut flowers that are fully open, but the petals should not have started to wilt too much. (A few wilted petals are all right — they will be eliminated in processing) The whole flower head should be cut, as this will encourage the plant to produce more blooms.

Note: In the 16th century crimson Damask roses were grown by the acre, so cooks of that time had access to roses that a Caidan cook can only dream of. It is not necessary that all your petals be from red roses — any scented rose will do. I have made both rose petal jam and rose syrup using a mixture of petals of all colors, and as long as at least some of the petals are red, the results have still been dark red.

Once all the roses have been cut, carefully remove the petals from the rosehip, discarding any petals that are wilted or damaged. If at all possible, this should be done outdoors because there will be an incredible number of insects inside each flower (no pesticides, remember?) and you’ll want to keep them outside the house.

At the base of each petal is a small white patch, called the “nailes” by John Gerard and the “whights” by Lady Elinore Fettiplace. It should be removed using a small sharp scissors, as it will add a bitter taste to the final product.

Finally, the petals should be rinsed thoroughly with cool running water and allowed to air dry. They are now ready to be cooked.

The first rule of preserving, like that of medicine, is “Do no harm,” which means (in our case) do not let bacteria get into your preserves. Before you start, wash all pots, utensils, and kitchen surfaces with hot, soapy water and rinse well.

To Make A Conserve Of Roses

Take Red Rose budds, Cut of the whights then boyle them in water untill they bee very tender, then wey to every pound of Roses and water 3 poundes of sugar and boyle yt together till it be thicke enough stirr yt still on the fire and untill yt be colde then put yt in glasses and preserve yt to yor use.

– Elinor Fettiplace’s Receipt Book, compiled 1604

Conserve Of Red Roses

The same can be made another way, but better by many degrees: take the Roses at your pleasure, put them to boyle in faire water, having regard for the quantity; ,for if you have many roses, you may take the more water; if fewer, the less water will serve: the which you shall boyle the least three or foure houres, even as you would boyle a piece of meat, until in the eating they be very tender, at which time the roses will lose their colour, that you would think your labor lost and the thing spoiled. But proceed, for though the roses have lost their colour, the water has gotten the tincture thereof, then shall you add unto one pound of Roses, foure pound of fine sugar in pure powder, and so according to the rest of the roses. Thus shall you let them boyle gently after the Sugar is put thereto, continually stirring it with a wooden Spatula until it be cold, whereof one pound weight is worth six pound of the crude or raw conserve, as well for the vertues and goodnesse in taste, as also for the beautifull colour.

– John Gerard, The Herbal, or General History of Plants

You will need:

1/2 pound rose petals, cleaned and trimmed as above

1 cup water

3 or 4 pounds sugar

2 8-oz (or 4 4-oz) jam jars processed according to directions on the package.

Put the petals and water in an enamel or other non-reactive pot, cover and stew gently for about 30 minutes until all color has been leached out of the petals. (Don’t worry about this — they’ll turn red when the sugar is added.)

Increase heat and add the sugar, one pound at a time, letting each pound dissolve completely before adding the next. Three pounds of sugar, as Lady Fettiplace suggests, results in a somewhat runny jam, while four pounds of sugar will most likely cause the rose petals to crystallize (not necessarily a bad thing) in the jar. The amount of sugar you add will depend on the result you want.

When the last of the sugar is dissolved, bring the mixture to a boil. Boil until the mixture thickens and a drop placed on a cold plate forms a skin when it is pushed with a spoon. Overcooking the mixture can result in the entire batch of jam crystallizing once it is in the jar.* Remove from heat and quickly ladle the jam into the hot sterilized jam jars. Carefully wipe any spilled jam away from the outside of the jars, then apply the seals and rings.

*If this happens, the jam can be re-melted by putting the entire jar (unsealed) into a bowl and adding hot water up to about an inch below the lip of the jar. Leave the jar there (changing the water as needed to keep it hot) until the jam is sufficiently melted.

Note: because the ratio of rose petals to sugar is so high, this jam does not need to be heat-processed after the jars are sealed. The high sugar content acts as a preservative and prevents the growth of bacteria. The jam should be refrigerated after the jar is opened.

This jam has a very delicate flavor and can be used for any purpose as any other flavor of jam except one: peanut butter sandwiches. The strong flavor of peanut butter totally overwhelms rose-petal jam. Lady Fettiplace used her conserve for cheer and comfort the ill, incidentally while hiding the flavor of her more noxious medicines. Herbalists tended to prescribe it for coughs, colds and lung complaints.

A Singular manner of making the sirup of Roses

Fill a silver Basin three quarters full of rain-water or Rose-water: put therein a conveient proportion of Rose-leaves: cover the basin and set it upon a pot of hot water (as we usually bake a custard) in 3 quarters of an houre, or one whole houre at most, you shal purchase the whole strength and tincture of the rose: then take out those leaves, wringing out their liquor gently, and steepe more fresh leaves in the same water: continue this iteration seven time, then make it up in a sirup: and this sirup worketh more kindly than that which is made meerly of the juice of the Rose.

-Sir Hugh Plat, Delighes For Ladies, published 1609

To Make A Serop Of Roses

Take damask rose buds six handsfulls, & cut of the tops, and take a quart of faire running water, & put the roses therein, & put them in a basin & set them over the fire, that the water may be warm one day and night, then in the morning squise the roses hard between your hands out of the water, & put in as many fresh, & let them stand still on the fire, this doe nine times, then take out your roses, cleane out of the water, & put in as much sugar as will make it sweet, and boyle it till it come to a serop; you must put to everie pinte a pound of sugar.

– Elinor Fettiplace’s Receipt Book, compiled 1604

You will need:

Clean and trimmed rose petals

Water

Sugar

Put two handfuls of petals into the top of an enamel double boiler (or a Pyrex casserole suspended over a pot of water) with just enough water to cover them and put them over gently simmering water. Although Lady Fettiplace states that it should be on the fire for a day and a night, Sir Hugh Plat points out that 45 minutes to a hour will “purchase the whole strength and tincture of the Rose.” An hour is long enough for even the darkest petals to bleach absolutely white. Take the mixture off the fire and allow it to cool enough to be handled, then remove and discard the petals, squeezing as much liquid from them as possible. Put in two handfuls of fresh petals and repeat the procedure.

Lady Fettiplace’s recipe calls for this to be repeats nine times, although Sir Hugh recommends seven changes and other contemporary recipes call for as few as three changes. How many changes you will get depends on how many rose petals you have. No additional water is added for each successive change, so the liquid will decrease in volume as it becomes concentrated.

The end result will be a dark red, almost black, liquid. For every pint of liquid, add one pound of sugar and boiled the mixture gently until it thickens. The longer it is boiled, the thicker the resulting syrup be, but do not cook it too much or it will lose its fresh rose taste and aroma.

Pour the finished syrup into a clean bottle or jar with an air-tight closure, let it cool, and store it in the refrigerator, where it will stay good for years, if it lasts that long.

Lady Fettiplace used this syrup to flavor cool drinks in summer and to also hide or counteract the strong flavors of some of her medicinal remedies. John Gerard recommends rose syrup to cool the heat of fevers and agues, as a thirst quencher (taken with white wine) and for mild stomach problems. (Actually, he goes on to describe in medically gruesome detail the benefits to the whole digestive tract.) Nicholas Culpepper recommended it to cool the liver and comfort the heart and notes that a small dose taken every night will help with regularity. Banckes Herbal recommends syrup of roses for “feble sicke melacoly and colorike people.”

Bibliography

Culpepper, Thomas. Culpepper’s Complete Herbal. London: W. Foulsham & Co., Ltd.

Digbie, Sir Kenelme. The Closet of the Eminently Learned Sir Kenelme Digbie Kt. Opened. London: H. Brome, 1669

Gerard, John. The Herbal, or General History of Plants. Revised 1633 by Thomas Johnson. New York: Dover Publications, 1975

Hillman, Howard; Loring, Lisa; MacDonald, Kyle. Kitchen Science. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company 1981, 1989

Plat, Hugh. Delights for Ladies. London: Humfrey Lownes, 1609

Rohde, Eleanour Sinclair; The Old English Herbals. New York: Dover Publications 1971

Rohde, Eleanour Sinclair; Rose Recipes from Olden Times. New York: Dover Publications 1973

Spurling, Hilary. Elinor Fettiplace’s Receipt Book: Elizabethan Country House Cooking. Compiled 1604. New York: Elizabeth Sifton Books/Viking Penguin, Inc. ,1986

—

Copyright 1998 by Sharon Cohen, P.O. Box 7487, Northridge, CA 91327-7487.

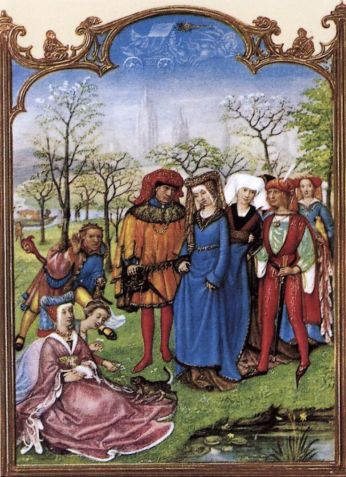

June 22nd. St John’s Day is June 24th with St. John’s Eve being June 23rd. So yes, Midsummer occurs just a few days after the Summer solstice! By tradition Midsummer was a time of revelry and bonfires. Shakespeare even has Olivia in the play Twelfth Night say, “Why, this is very midsummer madness,” knowing his audience would be well aware of the merriment of a Midsummer eve and day.

June 22nd. St John’s Day is June 24th with St. John’s Eve being June 23rd. So yes, Midsummer occurs just a few days after the Summer solstice! By tradition Midsummer was a time of revelry and bonfires. Shakespeare even has Olivia in the play Twelfth Night say, “Why, this is very midsummer madness,” knowing his audience would be well aware of the merriment of a Midsummer eve and day. Was looking up some ways that cooks in the Lowlands (12th Century Western Europe) would of used up old bread from the days before. Nothing went to waste in that society and with no real refrigeration and limited resources for ingredients, it made sense to use up as much as possible.

Was looking up some ways that cooks in the Lowlands (12th Century Western Europe) would of used up old bread from the days before. Nothing went to waste in that society and with no real refrigeration and limited resources for ingredients, it made sense to use up as much as possible. This is a year of a late Spring. Here in Michigan, we had scant snow in February, but it snowed off and on in April. One must move along and think seasonally, so one might as well look for recipes which specify spring. Here are a few English recipes mentioning the season.

This is a year of a late Spring. Here in Michigan, we had scant snow in February, but it snowed off and on in April. One must move along and think seasonally, so one might as well look for recipes which specify spring. Here are a few English recipes mentioning the season.

You must be logged in to post a comment.