This article was originally published in the July 97 issue of Ars Caidis and has been archived on Stefan’s Florilegium here. I asked Renata for permission to repost her articles here for my readers. Since Plums are a summer fruit (mostly here in California) I thought it would be timely to post something to do with plums.

Visions of Sugarplums

by Mistress Renata Kestryl of Highwynds

The dictionary defines a sugarplum as a small round or oval piece of sugary candy. English being the flexible language it is, the name could have come from the resemblance to a small plum. Or it could have come from actual plums preserved in sugar, a relatively new idea in 16th Century England. Prior to this time sugar was so expensive that it was used very sparingly, much as we would use a spice today. In the 1540’s, however, sugar started being refined in London which lowered the price considerably, although only well-off families were able to use it lavishly. Preserving with sugar allowed the sweet fruits of summer to be enjoyed all year round, especially during the holiday season.

16th Century cooks did not record their reasons for using one ingredient over another, although they seem to enjoy very much trading recipes and most of those who wrote down their recipes were scrupulous about attributing them to their original creators. Some recipes have delightful names such as “The Lord of Devonshire, His Pudding.”

Herbalists of the day, however, had a great deal to say about the produce and seasonings used. John Gerard, whose Complete Herbal was first published in 1597, says of fresh plums that they provide very little nourishment and moreover have a tendency to spoil quickly and taint any dish they are served in. Dried plums, or prunes, he says, are much more wholesome and he recommends them for problem in the digestive system. Thomas Culpepper, writing somewhat later, finds virtue in both the fresh and dried fruit.

Gerard also has a bit to say about sugar cane and the product of its juice, sugar. In addition to listing the benefits of sugar to the respiratory and digestive systems, he starts to list the culinary goodies which can be made with it. He then points out “it is not my purpose to make my book a Confectionairie, a Sugar Bakers furnace, a Gentlewoman’s preserving pan…” He also offers a thumbnail sketch of sugar refining.

Whether 16th Century cooks worried about the nutritional value — or lack thereof — of their holiday treats is, of course, open to conjecture. I invite anyone who has lived through a massive holiday baking session to ponder this question.

I first tried some 16th Century preserving techniques to make 12th Night gifts, and now understand why sugared fruit was a treat to be saved for special occasions. For one thing, sugared fruit is intensely fruit-flavored and unbelievably sweet, for another it is extremely time-consuming (but not difficult) to make. Fortunately for 12th Night gift-giving, the time to make sugarplums is during the summer, when plums are ripe.

TO DRIE APRICOCKS, PEACHES, PIPPINS OR PEARPLUMS

Take your apricocks or pearplums, & let them boile one walme in as much clarified sugar as will cover them, so let them lie infused in an earthen pan three days, then take out your fruits, & boile your syrupe againe, when you have thus used them three times then put half a pound of drie sugar into your syrupe, & so let it boile till it comes to a very thick syrup, wherein let your fruits boile leysurelie 3 or 4 walmes, then take them foorth of the syrup, then plant them on a lettice of rods or wyer, & so put them into yor stewe, & every second day turne them & when they be through dry you may box them & keep them all the year; before you set them to drying you must wash them in a litlle warme water, when they are half drie you must dust a little sugar upon them throw a fine Lawne.

(by the Lady tracy)

— Elinor Fettiplace’s Receipt Book, 1604

Sir Hugh Plat, in his Delights for Ladies (published 1609), seems to have more faith in his readers’ culinary skills, as his recipe is much simpler:

THE MOST KINDELY WAY TO PRESERVE PLUMS, CHERRIES, GOOSEBERIES, &c.

You must first purchase some reasonable quanity of their owne juyce, with a gentle heat upon embers, in pewter dishes. dividing the juice still as it commeth in the strewing: then boile each fruit in his own juyce, with a convenient proportion of the best refined sugar.

You will need:

1-2 pounds of plums (any variety) fully ripe but not too soft

lots of white granulated sugar (unfortunately I cannot be more exact)

a large, heavy saucepan, preferably enamel

a wire rack — a cookie cooling rack works very well — set up over a cookie sheet covered with wax paper.

Wash the plums, cut them in half and remove the pits (this is a lot easier if you’re using a freestone variety). Lady Fettiplace, you may have noticed, does not mention this step, and may have indeed preserved her plums whole. Since the resulting candy is incredibly sweet, I found that preserving the plums cut in half makes a more reasonable serving of the final product.

Do not peel the plums — the peel helps them keep their shape while cooking and colors the sugarplums, and most of the peel will come off during processing. The idea is to preserve each half as complete as possible, so you want to avoid breaking down the cellulose structure of the plums. Since the act of cooking, adding heat and moisture, is exactly what breaks down the cellulose structure of food, you will see the words “gently” and “carefully” often in the following instructions.

Put a thin layer of sugar in the bottom of the saucepan. Lady Fettiplace’s recipe calls for clarified sugar, because she was working with a less refined sugar than we have today. She would have done the last boiling of the sugar (the last step in modern sugar refining) herself.

Lay the plums halves, cut side down, on the sugar in a single layer. Add enough sugar to completely cover the layer of plums, then lay another layer of plums on top. Continue layering until all the plums have been used and are covered.

Put the pan on the stove over the lowest heat possible. The sugar needs to dissolve in the plum juices without burning. While this is happening, stir very gently and scrape the sugar away from the sides of the pan. Try to disturb the fruit as little as possible.

When all the sugar is dissolved, increase the heat until the syrup comes to a gentle boil. (If it boils too hard, it will break up the plums.) A “walme” is 16th Century culinary for a “warm” or a boiling up, i.e., bringing liquid to a boil. Let the fruit boil for one minute, then remove the pan from the stove. If you are NOT using an enamel pan, gently remove the fruit from the syrup with a slotted spoon and put it in a large shallow glass or ceramic bowl and carefully pour the syrup over it. If you are using an enamel pan, the fruit can stay in it. Carefully place a plate over the fruit to keep it submerged in the syrup. Cover with the pan lid or a clean dish towel and let soak for three days.

A note about sugar: Boiling sugar can cause severe burns. It is very, very hot and tends to stick to the skin like boiling oil. As if that wasn’t bad enough, it will also stick to your stovetop and counters with incredible tenacity. Be careful not to splash the hot syrup when transferring the fruit.

Another note: The soaking process should be at room temperature, which means that you can leave it out on the kitchen counter or on an unused stove burner. But beware of ants! If your kitchen is ant-prone, place the pan or bowl in a larger container that has a few inches of water in the bottom.

After three days, carefully remove the fruit and bring the syrup to a boil. Gently return the fruit to the syrup, bring to a gentle boil again and let boil for one minute. Remove from heat and repeat the soaking process. Repeat the boiling and soaking process one more time, for a total of nine days soaking and approximately 3 minutes boiling.

After the last soaking, remove the fruit from the syrup. Heat the syrup again and dissolve one additional cup of sugar in it. Let the syrup boil until it thickens somewhat (it may darken as well, depending on what variety of plums you’ve use), add the fruit again and allow it to boil gently for four minutes.

Remove the pan from the heat. With a slotted spoon, carefully remove the plums one at a time from the syrup and rinse the excess syrup away under cool, gently running water. Since no two plums are ever at exactly the same degree of ripeness, some of your plums will have broken up during processing. Never fear, they’ll taste just as good as those that kept their shape. If you wish, you may remove any peel that remains on the plums. (Ladies in the 16th Century would have removed the peel — I like the texture with the peel in place.) Spread the plums on a wire rack and put in a warm dry place. “Yor stewe” was a special drying stove in the 16th Century stillroom. In the 20th century kitchen, a gas oven with just the pilot light burning in it is perfect, but make sure you remove the plums before preheating the oven for dinner. I’ve lost more plums that way, and burned sugarplums are the stickiest mess you can imagine.

Turn the plums every other day. When the plums are almost dry (they should still feel a bit sticky) sprinkle each side with granulated sugar. Throw a fine Lawne, as Lady Fettiplace says, is to sift the sugar through a piece of fine linen, which is not necessary with modern sugar. The drying time may be anywhere from a few days up to about two weeks, depending on local weather. When the plums are completely dry, store in an air-tight container. Plums processed in July are still soft at 12th Night and are chewier, but still delicious, more than a year later.

I have tried this recipe with several varieties of plum. I find that the Italian plums (prunes) work well because they are free-stone. As they have a higher sugar content and less acid than other varieties, the final sugarplums are much sweeter than those made from other varieties. In addition, they tend to be smaller than other plums, which result in bite-sized sugarplums. Lady Fettiplace probably used the Damson variety, which is a tart plum with purple-black skin and green flesh, and is used today for jam and jelly. Unfortunately, I’ve never yet been able to find Damsons, but I’ve used home-grown Santa Rosa plums (which were a bit on the tart side and ended up being totally wonderful) and the ones sold in the market as Black plums and Red plums. All turned out equally well.

I’ve also processed peaches, apricots and figs this way, with good results, and I’ve seen similar recipes for candied citrus peel. Figs are not as juicy as the other fruits, so add one-half cup of water to the sugar at the beginning to allow the sugar to dissolve before it burns. Otherwise you’ll end up with caramelized figs, which are very tasty but probably were not served on 16th Century tables.

Bibliography

Culpepper, Thomas. Culpepper’s Complete Herbal. London: W. Foulsham & Co., Ltd.

Gerard, John. The Herbal, or General History of Plants. New York: Dover Publications, 1975

Hillman, Howard; Loring, Lisa; MacDonald, Kyle. Kitchen Science. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company 1981, 1989

Pratt, Hugh. Delights for Ladies. London: Humfrey Lownes, 1609

Spurling, Hilary. Elinor Fettiplace’s Receipt Book: Elizabethan Country House Cooking. New York: Elizabeth Sifton Books/Viking Penguin, Inc. ,1986

Western Garden Book. Menlo Park: Sunset Publishing Corporation, 1994

—

Copyright 1997 by Sharon Cohen, P.O. Box 7487, Northridge, CA 91327-7487.

. Permission granted for republication in SCA-related publications, provided author is credited and receives a copy.

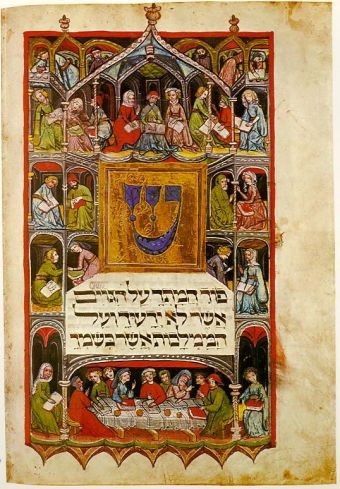

Was looking up some ways that cooks in the Lowlands (12th Century Western Europe) would of used up old bread from the days before. Nothing went to waste in that society and with no real refrigeration and limited resources for ingredients, it made sense to use up as much as possible.

Was looking up some ways that cooks in the Lowlands (12th Century Western Europe) would of used up old bread from the days before. Nothing went to waste in that society and with no real refrigeration and limited resources for ingredients, it made sense to use up as much as possible.

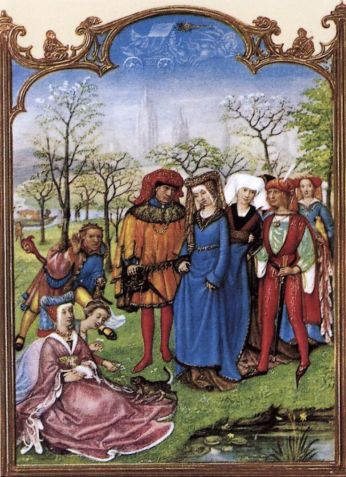

This is a year of a late Spring. Here in Michigan, we had scant snow in February, but it snowed off and on in April. One must move along and think seasonally, so one might as well look for recipes which specify spring. Here are a few English recipes mentioning the season.

This is a year of a late Spring. Here in Michigan, we had scant snow in February, but it snowed off and on in April. One must move along and think seasonally, so one might as well look for recipes which specify spring. Here are a few English recipes mentioning the season.

You must be logged in to post a comment.